Just received a distressing

letter from Sister Gitel, she is

actually starving with her family,

I will help her.

At the same time she states,

that the funeral of my late father

was the biggest ever held in

Sniatyn all ! old and young

alike went to pay the last honors

to my beloved father. I am

the saddest orphan alive

and I was deprived by fate of

the privilege to say Kadish

at his grave.

I feel now that his memory

is inspiring me to uphold

the dignity that was my his

fathers.

Shalom Le-nafsho

——————–

Matt’s Notes

I’m not sure why, but Papa’s description of his father’s funeral seems almost like something out of a fairy tale: the hillside of a European hamlet, covered with milling families, all gathered together to pay tribute to one of their leading citizens. This is consistent with Papa’s previous diary entry in which he described his adult melancholy as a feeling of “lost paradise,” as if the existence he knew in Sniatyn before coming to New York was somehow enchanted or blessed. Why, then, wouldn’t we expect him to romanticize his father’s funeral and the lost world it represented?

At the same time, Papa knows Sniatyn is anything but Paradise.* It’s a place where Jews — even Jews like his sister Gitel, the daughter of a beloved Talmud Torah teacher whose funeral was the largest the town ever saw — could go starving with their families. Papa had a couple of moments over the last few weeks when he felt overwhelmed by the responsibilities of supporting his family in Europe and even expressed some resentment over his siblings’ frequent requests for money, but thoughts of his father’s example have clearly relieved him of those feelings for the moment.

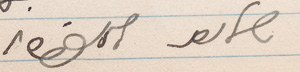

Papa concludes this passage with a Hebrew phrase similar to the one he used a few days ago in reference to a departed family friend. In that case, Papa seemed to write Shalom Le-efro, or “Goodbye to His Ashes.” Today’s phrase appears to be slightly different: Shalom Le-nafsho, or “Goodbye to His Soul.” Maybe he wrote the same thing in both entries, but they certainly look different:

Shalom Le-efro?

Shalom Le-nafsho?

Feel free to write or comment if you read these phrases any differently.

—————

* Sniatyn would become the very opposite of Paradise during the Nazi occupation. This article from the Guardian, pointed out by our friend Aviva, shows a photo that seems to depict the murder of several Jews in the Sniatyner woods during the massacre of 1942. The article goes on to question whether the photo is actually from Sniatyn, but it’s an interesting and touching read.

Hi Matt,

Regarding your question about the two Hebrew phrases, here are my thoughts:

– First, I admittedly don’t know to what extent either of these possibilities (shalom l’nafsho and shalom l’efro) were used in religious Jewish circles at that time.

– I will say that both myself (an American who speaks fluent Hebrew) and my wife (a native Israeli), as well as our friend (an Israeli author) are leaning towards the belief that both terms are the same, and that they’re both “shalom l’efro”.

– This is because of two reasons: (1) The second and third letters in both seem strongly to be an Aleph followed by a Peh; (2) It seems more logical that your grandfather would use the same term in mourning, regardless of the fact that each person held different emotional significance for him.

– The open question is: What is that weird line that he throws in above the Peh? I don’t know. In glancing at other posts, it seems there are lots of examples of him writing Hebrew, so we can piece together things by finding recurring representations.

– One last note: Add to the list of fascinating topics related to and researchable via this blog Hebrew linguistics a short time after the language was reinvented!

–

Hi Matt, Mike,

– I agree that both are the same phrase, and I would lean more towards l’efro than to l’nafsho from what it looks like.

– I think the horizontal line over the Peh is a rafe symbol used in Yiddish to mark a Peh as having a soft “ph” sound rather than a hard “p” sound. In modern Hebrew the differentiation is by having a dagesh (dot) inside the hard letter, but for someone accustomed to write Yiddish it would have been done by putting a horizontal line over the soft Peh.

– However, the term “shalom l’efro” (peace to his ashes) would seem to imply cremations, which I would think would hardly be an accepted practice in a Jewish community at the time. But it might just be part of the common phrase “afar va’efer” (dust and ashes) to refer to the dead.

Hi Matt, Mike,

– I agree that both are the same phrase, and I would lean more towards l’efro than to l’nafsho from what it looks like.

– I think the horizontal line over the Peh is a rafe symbol used in Yiddish to mark a Peh as having a soft “ph” sound rather than a hard “p” sound. In modern Hebrew the differentiation is by having a dagesh (dot) inside the hard letter, but for someone accustomed to write Yiddish it would have been done by putting a horizontal line over the soft Peh.

– However, the term “shalom l’efro” (peace to his ashes) would seem to imply cremations, which I would think would hardly be an accepted practice in a Jewish community at the time. But it might just be part of the common phrase “afar va’efer” (dust and ashes) to refer to the dead.

As Avi noted, shalom here is probably peace, rather than farewell. It’s one of those phrases that survived in English as “May he rest in peace.”

And so he should.