——–

Dearest:

I’m so blue because you didn’t feel well this

evening, I pray that when this reaches you, you

will be restored to good health again.

Instead of going to the touring agency, I called

up that office, they promised to mail to me immediately

a prospectus on tourist prices on various steamers, the

dates and departures and returns.1

Beloved: My mind isn’t at rest just because

of your indifference to my most ardent courtships, I

know that your so called acting of last night was

true to an extent.

It tortures my mind to live in doubt, Would you

have said those things if you really loved me?

You told me Sweetheart that I’m getting what I

want, its true, but my my life will be miserable

knowing that you [are] unhappy.

Can’t one whose love is holy and pure ask from

the only girls to reciprocate?

Especially when she is ready to trip to the altar

with him.2

I feel Sweetheart that the realization is dawning

upon you and that eventually to will find that

that you’re loving me a great deal more than you

think you do, and when the realization comes

you will keep faith with me and be content

with my life companionship and all that I’ll

be able to offer you.3

Don’t expect of me a sudden revolutionary

transformation, I will endeavor to raise my

standards step by step.

I’ve already learned (thanks to your urge)

the value of a $ and I’m clinging on to it

as soon as it comes my direction.

After all in this worst industrial crisis

in years when most everyone is affected, I can

./.

I can manage to save, and believe me I’ll

take care of it.4

It is very late now, and I have to rest a little

for tomorrows grind.

I will call you at 1:05, and please don’t refuse

when I ask to meet you at 6:15 on 42nd St.

God Bless You Darling Sweetheart

and countless kisses from your

own

Harry

———–

Matt’s Notes

1 – Papa and my grandmother must have been planning a trip to celebrate their engagement (they wouldn’t be married until a year after Papa wrote this letter, so I don’t think he was looking into their honeymoon arrangements already). With steamship travel as common as it was, they could have had in mind anything from a short jaunt up the coast to a longer ocean voyage, but in any event I’ll try to track down what the “tourist prices” would have been like in those days.

Update: In response to an e-mail inquiry, Michael at the shipping history site wardline.com tells me:

I have also looked though my files and come across timetables for NY-area steamship lines like the Merchants and Miners Line and Eastern S.S. Co. which had ships on shorter, tourist-oriented routes… rates range from $1.75 to $3.00 per berth (not room–generally 2 berths to a room) for short votages to up to $37.50 for one of the better private rooms on slightly longer voyages.

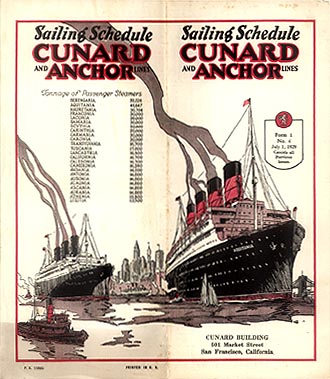

Michael also pointed me to the travel history site, Maritime Timetable Images, where we can find the following images of Cunard line brochures from 1929 and 1930:

–

We don’t know what kind of trip Papa was planning, but I’d wager that, due to the Cunard line’s popularity, he received at least one of the brochures pictured above.

2 – Oh, dear. If I’m reading this letter right, it looks like my grandmother must have said some really nasty things to Papa the previous evening: she wasn’t happy about marrying him; it shouldn’t matter to him because he was getting what he wanted; he was an unworthy candidate for her affections. It also seems like she tried to take a little of it back and tell him she only said those things because she wasn’t feeling well, but Papa clearly knew better.

3 – I’ve speculated quite a bit about why Papa pursued my grandmother so persistently in the face of her years-long efforts to dissuade him. I suppose the same theories apply to the question of how, now that her decision to marry him had apparently inspired her to treat him more harshly, he could remain so doggedly hopeful about their potential happiness. (In later years, those who knew them would but marvel at both the sharpness of my grandmother’s tongue and the contrasting evenhandedness of Papa’s attitude.)

4 – Throughout his diary and letters, Papa has shown himself to be both romantic and pragmatic, an idealistic dreamer who does not practice wishful thinking, a believer in God who would never count on divine intervention. From the moment he called himself a “nonbeliever in resolutions” in the New Year’s Eve entry of his 1924 diary, he has outwardly eschewed unrealistic concepts like “sudden revolutionary transformation”, though he would, in his darkest moments, believe in luck long enough to question his own. (Interestingly, the one resolution he did make in 1924, “to spend less and save more,” did not come to fruition that year but, according to this letter, finally did by 1930 despite the unfolding Depression.)

This belief in “step by step” progress shows itself in Papa’s approach to the most important pursuits in his life: the Zionist cause, for which he worked as a grassroots activist and to which he made countless small contributions over the course of decades, knowing he might never see it fulfilled; the garment industry labor movement, a perfectly literal demonstration of the way a class of people, seemingly powerless on their own, could, bit by bit, join together to wield great influence and improve their lot; and of course his courtship of my grandmother, a six-year affair that may never have led to an ageless romance but did lead to marriage, a child, and something like the life Papa dreamed of as a young man.