[no entry]

————————-

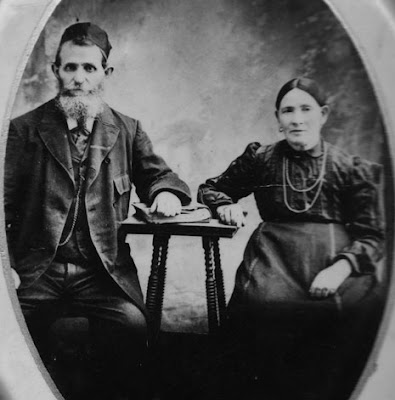

Papa was at the tail end of a forced week off from work on this day, a prospect he had dreaded since it gave him little more to do than think about his father’s recent death. Perhaps, though, the week off was good for him in a way; he wrote some beautiful words about his father a couple of days ago and, the next day, started to get a handle on his sadness by redoubling his commitment to helping his mother.

A bright spot on this day might have been the publication of an article he wrote the previous Monday for the Zionist weekly “Dos Yiddishe Folk.” I’ve discussed the article extensively in a previous post, but here’s the cover of the paper once again:

Meanwhile, the English-language New York Times ran a short wire story that Papa would have been far less excited to see in print:

HITLER WRITES A BOOK WHILE IN PRISON CELL; Tells Interviewer His Uprising Saved Germany From a Stinnes Dictatorship.

Papa obviously didn’t know Hitler was writing Mein Kampf or exactly what this article’s description of “postcards on sale everywhere with Hitler’s picture and evidence of the prisoner’s immense popularity” would one day mean. Still, it does remind us that whatever capacity for resilience he cultivates in the wake of his father’s death will be severely challenged twenty years hence when everyone else in his family dies at the hands of Nazi soldiers and, a few years after that, when one of his surviving sisters commits suicide. It also raises again the question of how someone could go through so much and remain, to the end, as generous of spirit, as forgiving, and as serene as Papa. The answers lie, perhaps, between the lines of his coming weeks’ entries, so we’ll have to watch them closely.