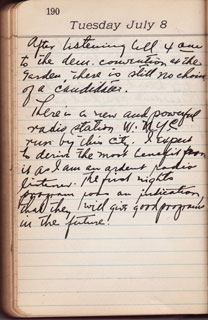

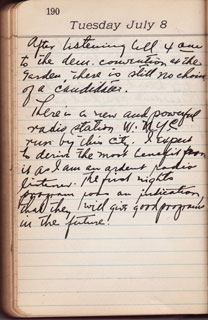

After listening till 4 am

to the dem. convention at the

Garden, there is still no choice

of a candidate.

There is a new and powerful

radio station W.N.Y.C.

run by this city. I expect

to derive the most benefit from

it as I am an ardent radio

listener. The first nights

program was an indication

that they will give good programs

in the future!

—————

Matt’s Notes

Papa felt compelled to listen to the Democratic Convention broadcast until 4 AM because the voting deadlock that had crippled the nominating process (and kept the convention in Madison Square Garden for a week longer than originally intended) had finally broken. William McAdoo, who seemed a stone’s throw from the nomination just a couple of weeks earlier, had finally faced the impossibility of his candidacy and released his delegates, as had all other candidates including New York Governor Al Smith.

The nomination, of course, was not going to be more than a door prize at this point. The 1924 Presidential conventions were the first ever to be broadcast on the radio and accordingly received unprecedented scrutiny. The Democrats’ public, drawn-out conflicts over how to treat the Klan and the League of Nations in their platform, as well as their comically protracted balloting, had pretty much sealed their party’s defeat in the upcoming general election.

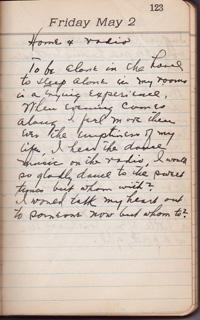

For those of you just joining us, we should note again that commercial radio was just finding its footing in 1924, and the novelty of the Democratic convention’s broadcast had New Yorkers enthralled. They clustered in public parks to listen to the action on public address systems, crowded the entrances of radio stores, and, if they were early adopters like Papa, stayed up until all hours with their headphones on. I suppose many people, including Papa (pictured below with his radio) must have spent the week of the Democratic convention, especially during its final days, in a hyper-attenuated, sleep-deprived state.

Yet even as New Yorkers wondered how the action at the convention was going to play out, they must have also wondered, in some way, at the strange cultural phenomenon unfolding in their city. New York may have been familiar with hosting large events, but until now there was no such thing as a broadcast “media event” of such scale and profile. Buildings were lined with bunting, the streets were full of parades and local businesses played host to packs of seersuckered delegates  from all over. But now, in addition to what they could see, New Yorkers had the odd, new ability to witness the raw goings-on inside the Garden. There simply had never been anything like it. The ubiquity must have been disorienting, maybe even thrilling. How did it feel? Like a child tasting ice cream for the first time? A blind person suddenly seeing a rainbow? (Or, more appropriately, someone discovering e-mail in the early 90’s?) What was it, exactly, they were a part of? How were they supposed to regard it?

from all over. But now, in addition to what they could see, New Yorkers had the odd, new ability to witness the raw goings-on inside the Garden. There simply had never been anything like it. The ubiquity must have been disorienting, maybe even thrilling. How did it feel? Like a child tasting ice cream for the first time? A blind person suddenly seeing a rainbow? (Or, more appropriately, someone discovering e-mail in the early 90’s?) What was it, exactly, they were a part of? How were they supposed to regard it?

But, let’s get back to the night of the 8th: At some point around 9:00, well before he realized he’d be up until the wee hours with the convention broadcast on WEAF, Papa tuned his radio to the 526-meter wave and caught the first sounds of WNYC. Today, New Yorkers of a certain demographic know WNYC as their city’s public radio station and take its existence for granted, but back in the 20’s municipally-financed radio was a strange innovation; it would not have arrived in New York but for the political savvy and tenacity of Grover A. Whalen, the city’s Commissioner for Plant and Structures.

The New York Times‘ coverage of the opening ceremonies quoted Mayor Hylan’s descriptions of the station’s rather broad goals:

To insure uninterrupted programs of recreational entertainment for all the people is one of the compelling reasons for the installation of the Municipal Radio Broadcasting Station. To assist the Police Department in the work of crime prevention and detection; the Fire Department in the expeditious employment of its land and marine equipment in fighting fires; and the Health Department in safeguarding the physical well-being of New York’s gigantic population are also some of the conspicuous services to be rendered by this municipal plant.

…

Municipal information, formerly available only after patient perusal of reports, is not to be brought into one’s home in an interesting, delightful and attractive form. Facts, civic, social, commercial and industrial, will be marshaled and presented by those with their subjects well in hand. Talks on timely topics will also be broadcasted. Programs sufficiently diversified to meed all tastes, with musical concerts, both vocal in instrumental, featured at all times, should make ‘tuning in’ on the Municipal Radio pleasant as well as profitable.

According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the night’s programming that so excited Papa included these highlights:

Clergymen of three different faiths pronounced invocations. Mons. Charles A. Cassidy, the Rev. Dr. Charles H. Nauman and Rabbi Bernard Drachman offered prayers. The program included several musical numbers in addition to addresses by many city officials. Vincent Lopez was there with his orchestra. The Six Brown Brothers saxophoned several selections. Miss Estelle Carey, who is widely known from her connection with the Mark Strand Theater in this boro, rendered a vocal solo. Several other features, including the Police Band and the Police Quartet, made the initial program pleasant to the musical ear.

Note that Papa almost never used exclamation marks in his diary, so I think the last line of this entry — “The first nights program was an indication that they will give good programs in the future!” — shows his excitement not only for the programming, but for the development of the radio medium in general. As I’ve mentioned before, Papa’s love of radio made him something of a proto-media geek — he likely built his radio set from a kit before commercial sets were commonly available, he listened obsessively (and, in his lonelier moments, wistfully characterized the radio as his “only companion”) and he recorded with boyish excitement the music, speeches, and sporting events he heard.

Alas, few recordings of 1924 radio exist (though WNYC has a simulation of their opening night’s programming on their 80th Anniversary retrospective Web site) though a few are still around. Earlier in the year, I paid a lunchtime visit to the Museum of Television and Radio and listened to a clip of Al Smith’s campaign manager, young Franklin Delano Roosevelt, announcing the release of Smith’s delegates to the roaring approval of the Democratic Convention crowd. I must admit I wasn’t prepared for how solemn I’d feel when I realized I was listening to the very sounds Papa must have heard himself. I sat there and stared for a while at my carrel’s desk. Some guy behind me chuckled aloud at the old sitcoms he was watching, and I felt offended somehow, as if he should have known how close I had just come to Papa.

——————

Thanks to Andy and Jennifer at WNYC for their help with this post.

——————-

References from The New York Times:

Other references:

————

Image Source: “One of the delegates to the convention who comes from Texas.” Library of Congress #LC-USZ62-132243. Image rights not evaluated, according to the LOC.

from all over. But now, in addition to what they could see, New Yorkers had the odd, new ability to witness the raw goings-on inside the Garden. There simply had never been anything like it. The ubiquity must have been disorienting, maybe even thrilling. How did it feel? Like a child tasting ice cream for the first time? A blind person suddenly seeing a rainbow? (Or, more appropriately, someone discovering e-mail in the early 90’s?) What was it, exactly, they were a part of? How were they supposed to regard it?

from all over. But now, in addition to what they could see, New Yorkers had the odd, new ability to witness the raw goings-on inside the Garden. There simply had never been anything like it. The ubiquity must have been disorienting, maybe even thrilling. How did it feel? Like a child tasting ice cream for the first time? A blind person suddenly seeing a rainbow? (Or, more appropriately, someone discovering e-mail in the early 90’s?) What was it, exactly, they were a part of? How were they supposed to regard it?