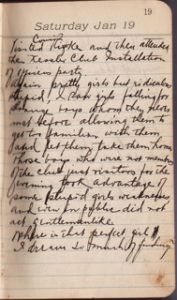

Visited Rifke and then attended

Visited Rifke and then attended

the Kessler Club Installation

of Officers (offices?) party.

Again pretty girls but ridiculous

stupid, I saw girls falling for

strange boys whom they never

met before allowing them to

get too familiar with them

and let them take them home.

Those boys who were not members

of the club just visitors for the

evening took advantage of

some stupid girls weaknesses

and even in public did not

act gentlemanlike.

Where is that perfect girl

I dream so much of finding?

———-

Matt’s Notes

Ever since co-ed parties were invented, sensitive young men have found themselves at the edges of the room, puzzled by the body language and easy laughter of those who make sport of sex. And so, piqued and frustrated, unable to penetrate the flirtatious fray, they have retreated to their journals, picked up their pens and issued some variation of the eternal lament: “why do the assholes get all the girls?”

At least that’s part of what’s happening here. Against his usually formal prose, Papa’s use of the word “stupid” to describe the women at the Kessler Zion club feels especially acidic; a less discrete writer (okay, I) might have ranged to the saltier side of the dictionary. Papa’s instinct for forgiveness, his reflexive ability to make the most gentle assessment of the least gentle people would become nearly legendary in my family, but here we see it shakier, nascent; only after twice calling the women “stupid” does he find the generosity to say they’re merely naive.

He makes no apologies for the men, though, who offend his sensibilities from too many angles. First, they are merely crude, and Papa is conscious of his distaste for their behavior (“even in public [they] did not act gentlemanlike”). Perhaps more deeply offensive, though, is the fact that they ply their crudeness at a club to which they don’t belong. As I’ve mentioned before, such clubs were crucial for the well-being and comfort of uprooted people like Papa, so party crashers at the Kessler Zion Club would have struck him like burglars in his family’s house.

Fueling his frustration from still farther beneath the surface is the way this party makes Papa question his footing. At 29, he was certainly among the older people there. Those cavalier boys and giggling girls might have been ten years his junior or even American-born. They may have had no use for his Edwardian sense of propriety, his grown-up politeness. Make no mistake, he would have been happy to take (or at least walk) a woman home, but such a possibility must have seemed urgently unlikely that night.

But perhaps, at the deepest root, his dismay is a just symptom of his resilient, baffling, beautiful romanticism. The boys and girls chatter in crass, ugly cadences, not in the poetic strains Papa would prefer. Yet notice how he asks “Where is that perfect girl I dream of finding?” rather than questioning whether such a girl could possibly exist; his belief in poetry is absolute. His anger, then, is not so much a bitter reaction as it is a necessary response to those who would shake what he knows to be unshakable. We see the strain such principles put on my grandfather as a young man, but to the end of his life he would remain capable of feeling only surprise when the world tried to disappoint him.

Update 1/20

My mother confirms that, even later in life, Papa was not a “hail-fellow-well-met,” as they would have said back in the day — that is, he remained gentle and somewhat serious-minded and never felt at ease with more jovial, back-slapping types. This is consistent with his disapproval of the the un-“gentlemanlike” men described above.