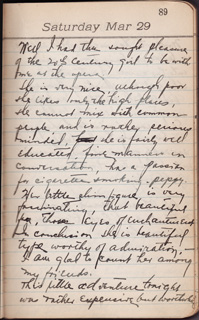

Well I had the sought pleasure

of the 20th Century girl to be with

me at the opera.

She is very nice, although poor

she likes only the high places,

she cannot mix with common

people, and is rather serious

minded, find she is fairly well

educated, fine manners in

conversation, has a passion

for cigarette smoking. peppy.

Her little slim figure is very

fascinating, that beautiful

face, those eyes of enchantment.

In conclusion she is beautiful

type worthy of admiration. —

I am glad to count her among

my friends.

This little adventure tonight

was rather expensive but worthwhile.

———

Matt’s Notes

Papa saw an opera double-feature on his date with the 20th Century Girl. The main attraction was Nicholas Rimsky-Korsakoff’s Le Coq d’Or, which concerns an Eastern European warlord (not unlike those who were making life miserable around the world for people like Papa) who gets his comeuppance for being a jerk. Papa certainly had a rooting interest in the outcome, and since I’m sure he knew the Pushkin poem, “The Golden Cockerel,” on which the opera’s based, he would have really enjoyed himself if he wasn’t too distracted by the “little slim figure” in the next seat.

Then again, if the 20th Century Girl’s education afforded her a working knowledge of opera, Papa would have had cause for worry; the performance apparently wasn’t that good. Though the New York Times had blessed the production, it had saved its highest praise for Rosina Galli-Curci. Alas, she was indisposed on the night of the 29th, thus casting a pall over the proceedings. Irving Kolodin, in his Story of the Metropolitan Opera, describes the consequences thus:

The large repertory was further varied by the return of Le Coq d’or on January 21 with Galli-Curci singing the Queen with excellent style and indifferent pitch, and Laura Robertson as the Voice of the Golden Cock. Giuseppe Bamboschek conducted a cast otherwise very much as before, and the production was Pogany’s…As one was to notice with increasing frequency, the heavy schedule often resulted in cast changes that not merely deprived the audience of a favorite voice, but substituted one of notably inferior quality. Thus, Sabinieeva for Gallie-Curci in Coq d’or…

Oh well. Perhaps the 20th Century Girl’s “passion for cigarette smoking” had her too distracted with thoughts of bodice-ripping ashtrays and tumescent match heads for her to notice the compromised work up on the stage. If not, she at least would have enjoyed the one-act opera that preceded Le Coq: Franco Leoni’s L’Oracolo, a tale of murder and intrigue (a “brilliant little ‘shocker’,” according to the Times) set in San Francisco’s Chinatown. I’m listening to L’Oracolo as I write this, but since I don’t speak Italian and am also sitting on a loud plane with a distressingly chipper flight crew chatting away behind me, much of the dramatic effect is lost.

In any event, there’s plenty of drama building in Papa’s delightfully 19th Century-style account of the 20th Century Girl. The phrases he uses, like “those eyes of enchantment” and “she is worthy of admiration,” sound like the words with which an awkward-but-secretly-loaded Jane Austen hero might stoically torment himself. Papa, of course, was not secretly loaded, and we know the 20th Century Girl “cannot mix with common people.” If Papa were writing a novel instead of his own life’s story, this description of her low tolerance for the low-born would certainly give the experienced reader pause.

———————–

Additional Notes

I still can’t get over how Papa cites the 20th Century Girl’s “passion for cigarettes” as one of her standout qualities. I’ll have to remember to credit myself with a “passion for bourbon” the next time I feel Maker’s Mark-induced shame creeping up on me.

Meanwhile, I’ve tried to figure out how expensive Papa’s night at the opera really was, but I’ve yet to learn what ticket prices were like in his day. Good tickets nowadays run $200 or more — the equivalent of $16 in 1924 dollars — but I doubt he spent that much. I’ll have to keep poking around, but if anyone out there can tell me more, please write to me or drop a comment.

——-

My mother adds:

Papa must have seen Galli Curci other times, because I remember him mentioning her a lot; I guess in an effort to improve my musical taste, which in those days ran toward the top 40. I think Papa probably disapproved of the passion for smoking of the 20th century girl, but was listing her many fine attributes as well as some things not so good, like not mixing with the common people. The fact that he counts her among his friends does not bode well for romance.

————

Sources

- Here’s the Coq d’or review from the New York Times

- And here’s the L’Amico Fritz and L’Oracolo review from the New York Times

- Here’s a good summary of L’Oracolo

Cigarette smoking for women at the time was considered risque and edgy, as was bobbing one’s hair.

The health risks of smoking were totally unknown and I’ve even seen ads that promoted cigarettes as being good for a sore throat!

Among South African Jews, even until the 50s, it was considered very racy for a woman to be smoking, driving a car and/or wearing trousers.

Anyway, from the perspective of a refined shtetl-born young man like Papa, the smoking would have significantly added to the mystique of the 20th Century Girl’s ‘modernity’.

In 1926, a ‘grand tier’ box at the Metropolitan Opera cost $60 per performance and could seat six, so that would be about $10 per head for presumably a superior seat.

In the description of the performance of March 29, I believe you’ve confused Galli-Curci and Galli. Rosina Galli (no Curci in her name) was the dancer who portrayed the Queen. The Galli-Curci who sang the Queen in three of the earlier performances had the first name Amelita. In addition, since the Coq d’or performance of February 15 was her last at the Met in the 1923-24 season, it appears that Sabinieeva was actually scheduled for the balance of the entire run. It wasn’t uncommon at that time for a leading singer to perform at the beginning of a run, with another singer taking over for the balance. One should also note that Galli-Curci had a heavy schedule at the Met that season – Barber, Lucia, Coq d’or, Traviata, Rigoletto – between January 16 and February 15, she sang 11 performances, averaging 1 every three days. If Galli-Curci had to bow out of Coq d’or due to sickness, it’s most likely she would have sung other performances after recovering. Instead, she didn’t return until virtually the same time period in each of her remaining years at the Met, in January/February 1925, ’26, 27, ’28, and ’29 (and December/January in ’29/30). –Rob