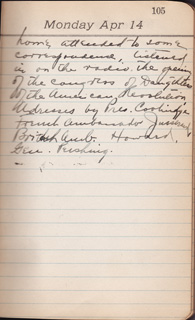

Home attended to some

correspondence, listened

in on the radio. The opening of

the congress of Daughters

of the American Revolution,

Adresses by Pres. Coolidge

French ambassador Jusserand,

British Amb. Howard,

Gen. Pershing.

——————–

Matt’s Notes

When Papa sat down at 8:00 PM and tuned in to WEAF, he listened to President Coolidge urge the Daughters of the American Revolution to get out and vote in the next election. It seems like an offhand moment by today’s standards, but Papa found it novel enough, as he did with many radio broadcasts, to record it in his diary.

As with its February 6 coverage of President Wilson’s funeral, AT&T distributed Coolidge’s speech by telephone line to three of its East coast radio stations: WCAP in Washington, WJAR in Providence, R.I., and WEAF in New York. The previous day’s New York Times saw fit to devote a column to the complexities and expense involved — the “remote control” technology it described had only been commercially practical for a year, and even so “the actual work necessary to prepare long-distance telephone lines for use in connection with radio broadcasting sometimes requires as many as sixty-five engineers.”

(A related article also excitedly reported on how “Hertzian waves” helped farmers research prices in multiple markets and figure out where to sell their goods. Said one Ohio farmer: “It is not difficult to make a radio pay dividends when rightly handled, and scarcely a week passes without my outfit yielding me something of value.”)

Coolidge had only been on the radio a few times since he took the reigns after President Harding’s death in 1923, but his voice resonated particularly well and helped make him an early broadcast celebrity. Coolidge quickly caught on to the medium’s potential as a campaign tool and broadcast a number of speeches, including the one mentioned above, in the run-up to the 1924 Republican Convention.

Since the audience consisted of women descended from America’s founders, the speech was appropriately full of patriotic rhetoric and historical references. Its central theme, though, concerned a more recent historical development, the effects of which had not, it seems, entirely permeated American life: the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote in federal elections. As Coolidge noted:

We have not yet been able to frame a very definite judgment of the changes that will be wrought in our public life, or our private life, because of this remarkable development. It has come so suddenly upon the world, chiefly within this first quarter of the twentieth century, that we have not had time to appraise its full meaning.

And:

I suppose that even among the Daughters of the America Revolution there are some women who sincerely feel that it is unbecoming of their sex to take an active part in politics. It is a little difficult to comprehend how such an attitude could be maintained by any women eligible to such a society as this…

Nevertheless, there are such, and to them I want especially to direct an appeal for a different attitude toward the obligations of the voter…

What must Papa have thought of such a speech? It’s hard to imagine a group more removed from his world of Zionist fundraisers and immigrant support societies than the Daughters of the American Revolution, and it’s hard to imagine an issue more baffling to him than the need to convince well-established, entirely assimilated Americans to accept their enfranchisement (still a baffling problem today, of course). Perhaps the mere thrill of listening to the President through his headphones distracted Papa from contemplating such things.