Saw for the first time how

they a big statue is put

together, part by part

was raised up and placed

accordingly.

It was at the 7th St. Park

very interesting

and it all was done in the dark

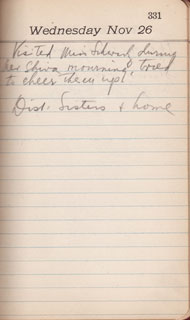

Wound up the Eve at the dist.

—————–

Matt’s Notes

Back in the early 1990’s, I lived half a block away from Tompkins Square Park, which sits between Avenues A and B and 7th and 10th Streets in the East Village. At the time, it was lined with snaking, unbroken rows of makeshift cardboard shelters built atop its benches, a source of constant tension between the people who lived in them and the cops who occasionally tried to kick them out. This tent city is long gone, but its image, no matter how many times I’ve revisited the neighborhood since then, remains my overriding memory of the park. It therefore took me a while, after I transcribed this entry last year, to realize that Papa’s “7th St. Park” was, in fact, Tompkins Square, and that I did, in fact, remember the statue of “The Pointing Guy” on the corner of 7th and A.

About a week ago, in anticipation of writing this post, I went down there with my wife, Stephanie, to check out The Pointing Guy and take a few pictures. I think I was smiling when we walked up to him, not only because our cab ride through Friday night traffic had blessedly concluded a few moments earlier, but because I was about to see one of the few landmarks mentioned in Papa’s diary that still exists. And there he was. The Pointing Guy.

Stephanie read about him from the plaque on the statue’s base while I fiddled with my camera and tried to get a decent picture in the dark. His name was Samuel Cox, and he was “a United States Congressman honored for having spearheaded the legislation which lead [sic] to paid benefits for postal workers. Letter carriers received a 40 hour work week and two weeks of yearly vacation as a result of congressman Cox’s initiative.”

The statue struck me as a little crude — Cox’s face looks half finished, and he stares forward and points at the sky like he wants to tell us, without looking back up, about a flying monster he just spotted — but I figured Papa, as a labor activist, would have admired Cox. Stephanie continued to read about how “the letter carriers of 188 cities” commissioned the statue in Cox’s honor, and how it originally stood at the intersection of Fourth Avenue, Lafayette Street and Astor Place near Cox’s former home on East 12th Street. Then her voice rose a little when she read the next bit: “In November 1924 it was relocated due to a street widening project to the south-west corner of Tompkins Square Park.”

I wouldn’t say I was stunned, exactly, when she read this, because I was still able to talk and move, but I did need to remind myself to breathe. I’d been writing for the whole year about Papa’s life in 1924, and I’d researched some things and confirmed the details of others and speculated on his thoughts and feelings, but this was the first time I’d had this sensation, the first time I’d been in same place he stood at the same time of year, the first time I’d looked at the same thing he saw and thought: It’s true. This really happened. Papa was here and it was just like this. Papa was alive.

But why did Papa write about it? As I mentioned yesterday, it’s sometimes hard not to think about what moments like this would mean if Papa’s diary were a novel, if the scene’s inclusion had some intended significance. Why was Papa so fascinated with the image of a man coming together in the dark, becoming rooted to the earth, making a permanent home just blocks from where Papa lived? Did Papa, after years of missing the family he’d left in the old country, after years of feeling unmoored, after years of feeling like he would never belong in one place, see in this statue something he longed for? Did this image of a man coming together in the dark remind Papa of the hidden changes he was experiencing, changes wrought by his attempts to put away childish things in the wake of his father’s death?

Stephanie and I went to a karaoke bar after we visited the statue. She likes to sing and I like to watch her and see the way she gives herself over to it, content and smiling through each note. I was a little distracted, though, still thinking of the statue. I grabbed a piece of paper and wrote down something I figured I’d hold onto for when I wrote this post. Here it is, edited slightly to correct for mild drunkenness:

For all his worries and for all he had been through, Papa forgot everything for a moment. He simply stood, with childlike fascination, so intrigued and absorbed that he later felt the need to write it down in his diary. And there I just was, in the same place, in the same place where my Papa, my beautiful Papa, stood and smiled, his face upturned, watching the statue go up as if there was nothing else to think about in the world.

We got home late that night and I fell asleep and dreamed of a time machine, a simple stone slab that would send me to the past when I stretched out on it. And I went back to visit myself when I was four years old and Papa was with me, and I was playing baseball, and I ran back to sit with him after I made an out, and I watched myself and worried, sure that at any moment I would become upset, or that someone would say something to upset me, about how I didn’t get a hit. I watched and watched but my young self just kept smiling, sitting next to Papa, who took me on his lap so we could enjoy the game together. And in the dream I thought: This really happened. Papa was here and it was just like this. Papa was alive.

He “would have been an actor of world-wide reputation if he had been unable to sing,” read

He “would have been an actor of world-wide reputation if he had been unable to sing,” read