3rd day of Shiba.

3rd day of Shiba.

Memories of my beloved father travel

through my mind, oh my heart is

aching so,

This evening after prayer service [they] told

me the old Hebrew consolation

which touched me so.

In my sorrow and grief the visit

of friends offering consolation relives

my suffering a little, Among todays

visitors were Cousins Mrs. H. Breindel

Sheindel Breindel, Badiner, Lemus

and Gravitzky, Sara Alter and

Mamie from the Shop.

I shall devote myself to the worship

of God and say Kadish for the memory

of my dear father.

—————

Matt’s Notes

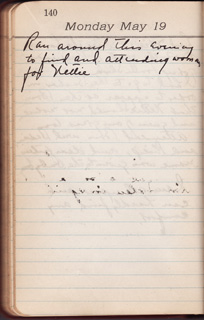

The “old Hebrew consolation” Papa mentions above can be written in English as hamkom yenachem etchem betoch she’ar aveilei tzion ve’yrushalaim and means “May you be consoled among the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem.” Here it is in Papa’s handwriting:

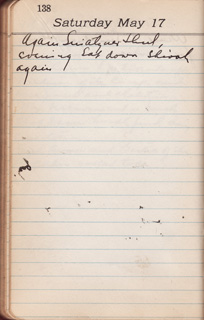

And for those not familiar, I should explain that shiva or “sitting shiva” (Papa spells it shiba in this entry; b’s and v’s are often interchangeable in Hebrew transliteration) refers to a week-long mourning period following the death of a loved one. The close family of the deceased follow a number of rituals during this week: they recite prayers, go to synagogue, and will sometimes cover their mirrors, eschew chairs for boxes, and refrain from personal grooming to deny themselves comfort and vanity.

It is also considered a good deed for friends to visit the homes of the bereaved. This explains the lists of people Papa records in his shiva entries, including a number of people we’ve met before (his cousins the Breindels and Herman Dunst, B’nai Zion brothers Lemus, Zichlinsky, and Shapiro) and some new characters (Badiner, Sara, Mamie and Pregev from work, and Aunt Golde). In keeping with tradition, Papa’s visitors would have brought food, helped out around the house and refrained from initiating unnecessary conversation in order to let him and his sisters focus fully on mourning their father, Joseph Scheurman.

How many had heard stories about him from their parents, or had their own stories to tell of his advice, methods, and habits? How well did they know the tones of his voice, the look of his hand as he pointed at a page, the way he positioned his paralyzed arm? How many had sat beside him while he explained a difficult concept, nodded their heads, met his gaze? As Papa sat and said

How many had heard stories about him from their parents, or had their own stories to tell of his advice, methods, and habits? How well did they know the tones of his voice, the look of his hand as he pointed at a page, the way he positioned his paralyzed arm? How many had sat beside him while he explained a difficult concept, nodded their heads, met his gaze? As Papa sat and said