[no entry]

————

Papa leaves his diary entries blank for the next few days, so I’m going to add a few pages to the site I’ve been meaning to work on for a while. First up, a new “Sound and Video” page, accessible from the left navigation, with a collection of all the audio and video files associated with Papa’s diary.

(Now that’s interesting: all this thinking about music and Papa leads me to remember that he used to sing “I Love You, a Bushel and a Peck” to me quite a bit, or at least that’s how it seemed to me. I haven’t thought about that in decades. I wonder how many other memories like this are still waiting to be tapped.)

The contents of the “Sound and Video” page includes:

January 1: The Volga Boat Song was played in the New Years Eve concert Papa attended. Here’s a version from Radio Blog Club:

—————————-

Papa recounts the story of a young Jewish woman who plays Schubert’s Serenade for immigration officials in order to qualify for an artist’s exception to the Jewish immigrant quota laws. It’s here at Radio Blog Club:

——————-

Papa describes how he listened to a boxing match in which Jewish boxer Abe Goldstein took the bantamweight title. We don’t have any footage of Golstein’s fight, but YouTube does have this 1922 fight featuring Benny Leonard, who was perhaps the most famous Jewish fighter:

———————

“Always blues, blues, even the radio is sending me blues through the air,” said Papa one rainy April day. We can’t be sure what he listened to, but here’s 1923 Bessie Smith recording of “Down Hearted Blues” from Last.fm:

And here’s a recording of “Who’s Sorry Now” by the Original Memphis Five from Archive.org:

—————–

Papa frequently says he listens to an ensemble called The Gypsy String Orchestra on the radio, and while I haven’t yet found one of their recordings, this 1914, Gypsy-influenced Berkes Bela tune from archive.org might be in the ballpark:

—————-

Papa lists a number of songs the Gypsy String Orchestra played on the radio that day, among them:

“Indian Love Lyrics,” which surely sounded a lot like this 1921 Edison Diamond Disc recording from the Library of Congress:

A “Gypsy Chardash” along the lines of this 1920’s-ish recording by Bibor Olga Ciganyzenekara (Olga Bibor’s Gypsy Ensemble) at Archive.org:

Papa didn’t mentioned the “Gypsy Love Song” specifically, but I thew in this 1923 recording of it, also available at Archive.org:

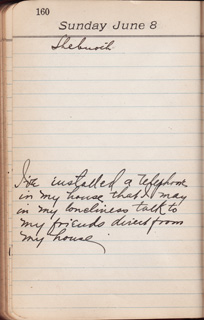

have induced me to see

have induced me to see