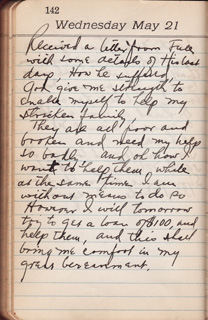

My Fathers Farewell to me

A beautiful Spring night at the

foot of the hill where my hometown

Sniatyn lies, at the Railroad station

early in June 1913, my father went

to bid me farewell on my long Journey

to America.

The train is waiting, a long

embrace a kiss, tears streaming

down from his eyes,

Did he have a premonition that

we would see each other no more?

The train is moving out slowly

and by the light of the moon I

could see through the window in the

distance my father [olam haba] weeping

and wiping his tears.

———-

Matt’s Notes

I hesitate to intrude on Papa right now, but if you’re interested to know, here’s what comes to mind when I read this passage:

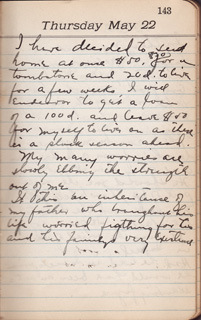

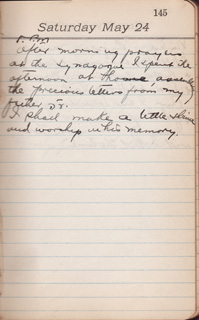

Somewhere around 1977 or 1978, my fifth grade teacher assigned my class a project called “Where Are My Roots?” for which we all had to write a report on our family histories. (The T.V. miniseries Roots, about an African-American family’s enslaved ancestors, was all the rage back then and had touched off a bit of a genealogy craze.) My report was about Papa’s emigration from Sniatyn, and though I don’t remember much about it, I know the centerpiece was a photocopy of the above entry. (My mother picked it out and my father “Xeroxed” it at his office, whatever that meant).

This sad, sweet passage was my first introduction to Papa’s diary, and though I didn’t quite understand its context (I hadn’t read the whole diary and didn’t know Papa wrote it in the wake of his father’s death) I was fascinated with its structure and scope: It seemed soaring, lyrical, surprisingly literary in the way it switched tenses, familiarly cinematic in its description of Papa’s last, dwindling look at his weeping father from the window of a moving train. From my young perspective, these words felt epic in scale, like they opened onto infinity, and until I transcribed them last year I thought they went on for pages.

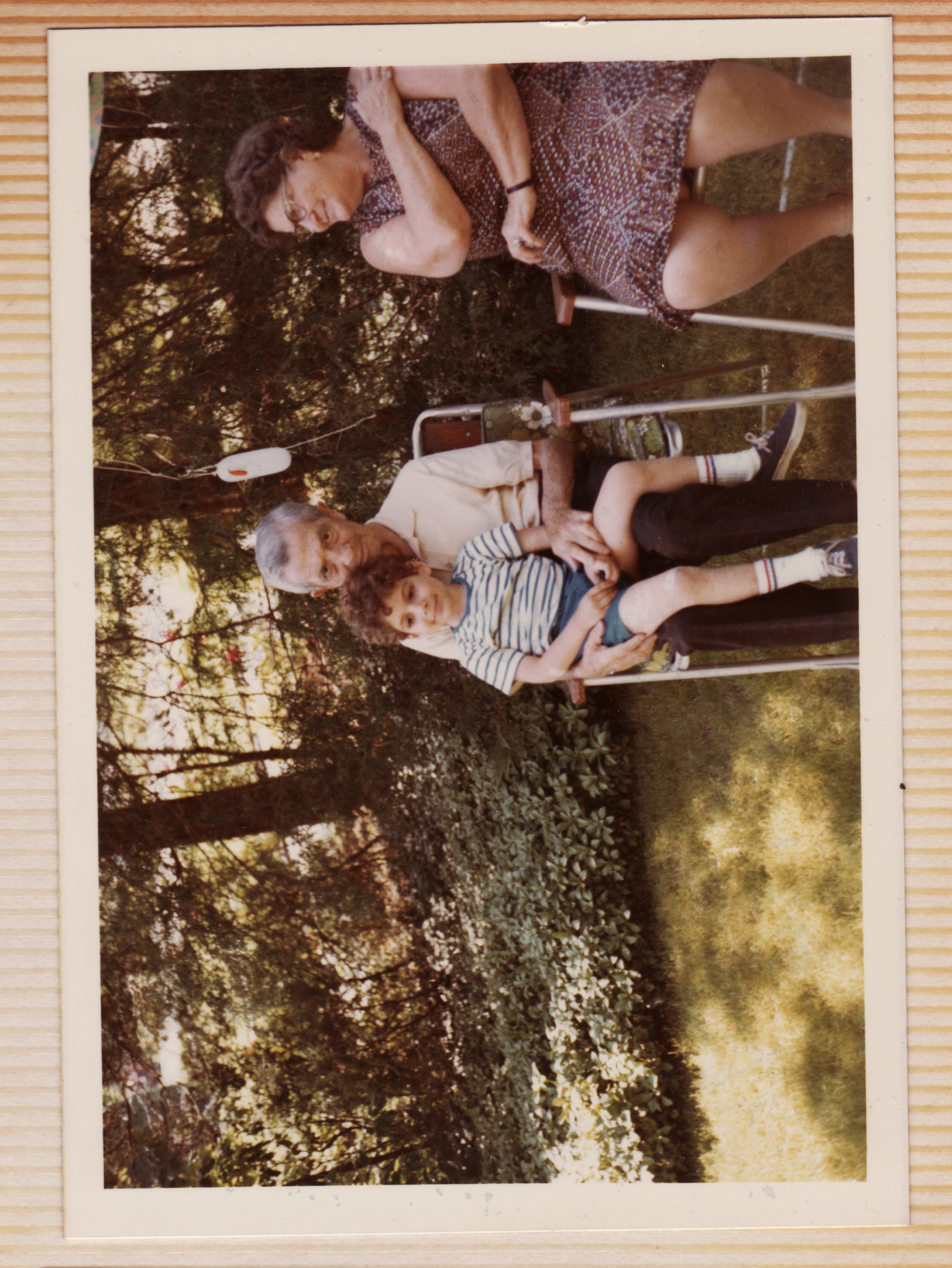

When I was a child I used to imagine that Papa’s ghost was looking out for me, hovering just out of sight over my shoulder. I was, in fact, terribly afraid of ghosts and spent many nights awake, under my covers, hiding from them. But to fear something is also to acknowledge its existence; was I willing, I ask rhetorically, to believe the world was full of ghosts just to convince myself Papa’s could still be with me? (It occurs to me now that I also used to think the ghosts in my house lived in a chair my grandmother gave us, a chair that for years occupied the apartment she shared with Papa.)

I mention this because I think it helps explain why, at eleven, this passage felt so important to me. I would not have been able to articulate how much I missed Papa or how much I longed for the lost feelings I associated with him. But to read his words was to hear the gentle murmur of his voice; to become lost in his prose was to feel his warmth; to see him wonder at his father’s “premonition that we would see each other no more” was to experience his idealistic optimism (anyone else would have known that he was saying goodbye to his father for good that night in Sniatyn, yet even eleven years later he chose to interpret the inevitable as a sign of his father’s wisdom).

Though it is, in reality, just one small page of an old pocket diary, this entry has indeed kept Papa with me for the last thirty years. I have hoped to revisit it, I have hoped to understand it more fully, I have hoped it might hold something more for me. I have hoped, each time I sit down to write, that I might one day compose something as spare and perfect and beautiful. But mostly I have hoped to be like Papa because I will never see him again. I will never see him again, even if he is just behind me, over my shoulder.

.

.