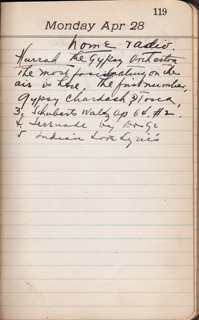

Matt’s Notes

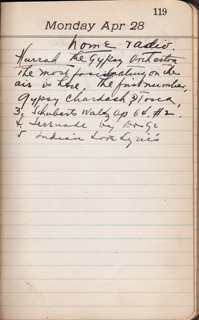

home radio

Hurrah the Gypsy Orchestra

The most fascinating on he

air is here. The first number,

Gypsy Chardash 2) Tosca,

3. Shuberts Waltz op 64#2

4. Serenade by Drigo

5 Indian Love Lyrics

—————

Matt’s Notes

If you’re at all interested in the evolution of American media, Papa’s accounts of his radio listening are truly precious artifacts. They allow us to witness a moment of enormous transition in our culture, when the broadcast industry was barely two years old and, like a two-year-old child, was growing furiously, dashing about like mad on its newfound legs, and shouting its head off even though it didn’t quite know what to say. It’s amazing to think that just three years before Papa wrote this entry, “wireless” communication was known only to military personnel and the few crazed enthusiasts willing to build their own radio transceivers and spread the broadcast gospel (not that there was always much of a distinction in the early days, since many engineers who served in World War I were recruited from the ranks of these ur-nerds)1.

It looks like Papa was a bit of a technical enthusiast himself. Though all-in-one radios with cabinet configurations or Victrola-style horn speakers were commercially available in 1924, the photo below shows him listening to a much earlier radio set:

The headphones he’s using, along with the overall messy look of the radio, indicate that it was most likely hand-built:

It also looks like Papa’s early radio enthusiasm reflected the broader Jewish community’s attitudes of the day; radio listings appeared in the Daily Forward (the influential left-leaning Yiddish language newspaper) as early as 1923. Papa undoubtedly checked out these listings every day, and maybe even let out a little “hurrah” when he saw a mention of his beloved Gypsy String Orchestra, “the most fascinating on the air.” (It’s interesting to note that the expression “on the air” was in circulation even at this early point in broadcasting history.)

The phrase “Gypsy String Orchestra” refers generally to a type of music ensemble, but in this case probably refers specifically to a group of New York-area musicians known for their appearances at such venues as Cafe Royal, The Rainbow Restaurant, and the Parkway Restaurant.2 Few recordings of 1920’s radio exist so it’s unlikely that we’ll ever know exactly what Papa listened to, but the wonderful Internets do afford us a chance to hear some early recordings of the songs he mentions above.

Here’s a 1921 Edison Diamond Disc recording of “Indian Love Lyrics” from the Library of Congress:

And here’s a 1920’s-ish “Chardash” (a.k.a. “tsardas,” “czardas,” “tzardash,” etc.) from Archive.org:

For good measure, here’s a “Gypsy Love Song” from 1923:

According to our friend Jill, who knows about such things, a Tzardash is technically more of a Hungarian folk form than truly Romani (i.e. more Gypsy-like than Gypsy) and points out that “in parts of austria and the old austro-hungarian empire– and still today in vienna– there are hungarian musicians who travel around and play hungarian folk music in the street. but i could see how one could take them to be gypsies or conflate it with gypsy music.” Papa probably did exactly that, though I expect less because he was Austro-Hungarian than because it was common practice in the 20’s to label Hungarian music as “gypsy” — or at least is was for the Gypsy String Orchestra and the group that recorded the above Tzardash, Bibor Olga Ciganyzenekara or (Olga Bibor’s Gypsy Ensemble).

———–

Update 4/29 — Well, that was fortuitous. I just stuck the “Gypsy Love Song” clip on this post because it happened to be on Archive.org, not because Papa mentioned it specifically. But, my mother just wrote to say “I can remember, as a little girl, Papa singing the Gypsy Serenade to me. What lovely memories this evoked.” How about that.

————

References:

1 – I got this from Erik Barnouw’s A Tower in Babel: A History of Broadcasting in the United States to 1933.

2 – Most of the information about the Jewish relationship to early radio and the cultural scene of the 20’s comes from Ari K., an academic advisor to this site. If you want to know more, you can purchase a copy of his dissertation at the University Microfilms (UMI) site. The site is stunningly shitty, but the dissertation number is 1392538.

I can’t find Web streams of the other pieces Papa mentions above, though most appear to be available in modern recordings (alas, I find no references to Schubert’s Op. 64 #2). I’m playing the above-mentioned “Serenade,” a selection from Richard Drigo’s ballet Les Millions d’Arlequin, right now. Anyway, here are some sources:

After working hours

After working hours