6:30P.M. This was certainly a mo-

notonous day so far what will happen later. –

9:45

I met at Breindel’s Clara the

daughter of Cousin Leizer, and

others, we went to Eva where

we had a most enjoyable eve.

Incl in the company were

Mr. and Mrs. Mendel, C, and her

friends.

I was glad indeed to receive

personal greetings from my parents

and other dear ones on the other

side, and that they are in good

health, which makes me

happier

The above mentioned

Clara Leizers arrived from Europe

recently.

—————–

Matt’s Notes

Papa has time-stamped this entry as he did on New Year’s eve, which makes me think he does this when he’s excited about what the evening has in store. In this case, when he penned his 6:30 paragraph he was getting ready to meet a recent arrival from “the other side.” With only the mails to keep him in touch with his large circle of family and friends in Snyatyn, this must have been a rare treat indeed. (The last paragraph of the entry is written in a light, straight hand, very different from his usual strong, slanted style. Perhaps he added this late at night, unable to sleep with news from home running through his head.)

Still, at the end of the evening he describes himself as “happier”, but not “happy,” which makes me sad. His English is too strong for him not to know the difference between the words. At best he’s trying not to tempt the keyn aynhoreh by seeming too cheerful. More likely though, it betrays how deep and indefatigable his sadness must have been.

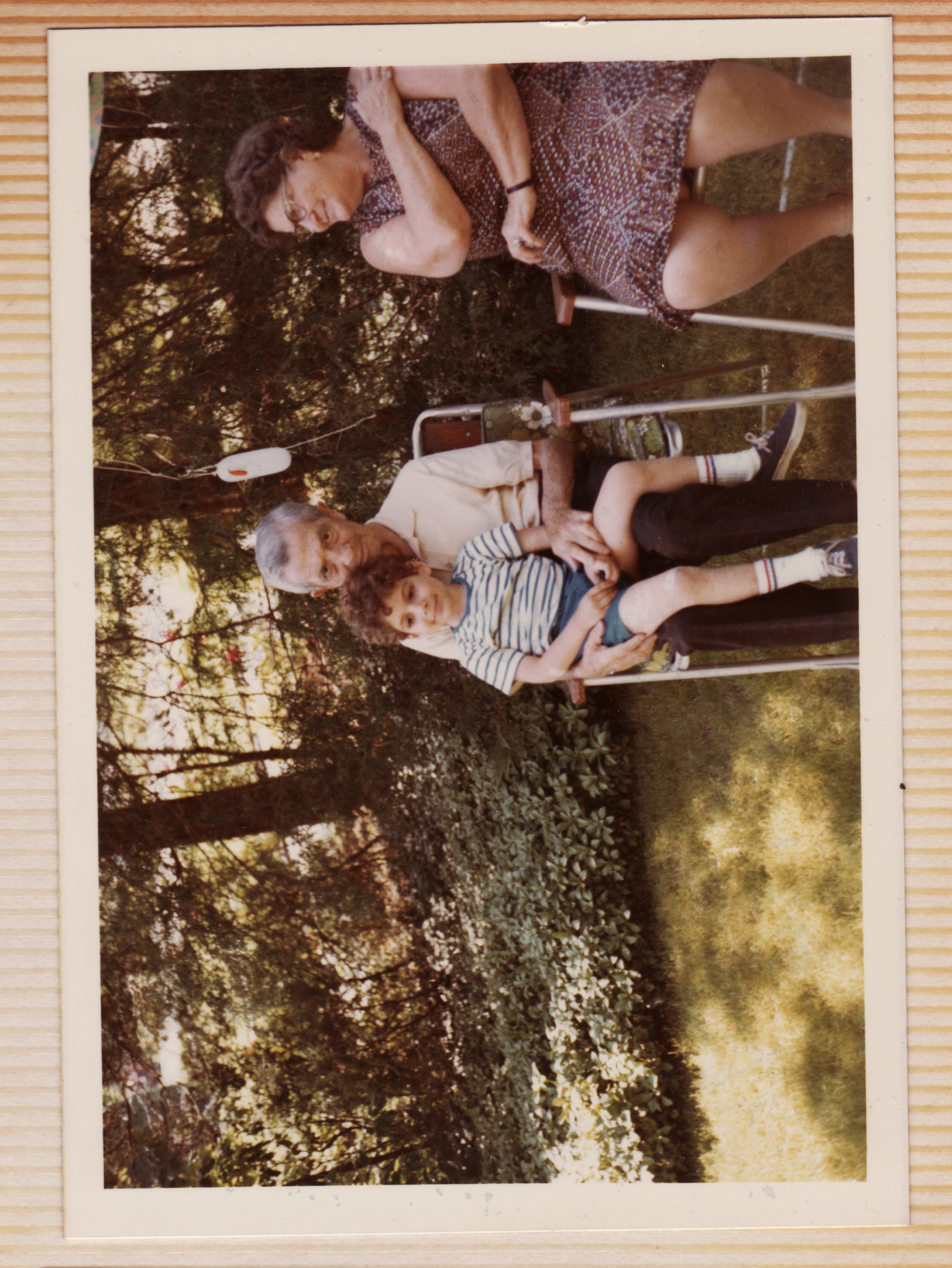

Sadder still: The “dear ones” he was so happy to hear about would almost all be killed by German soldiers a few years later. (Forgive me for laying it on so thick, but any mention of Snyatyn carries with it this cloud.) All the more remarkable, then, that when I knew him at the end of his life he radiated such personal joy and satisfaction. My mother has a photograph of him, sitting on our back lawn lawn, surrounded by his grandchildren in the sunshine, beaming kvelling with total contentment. In the end, he had all he wanted, and all the sadness of his youth, sadness so deep he wouldn’t allow himself the use of the word “happy”, was obliterated. It makes me want to send him a packet from the future with that photograph and a note saying “Papa, this is you.”

————-

Updates

My birthday today according

My birthday today according