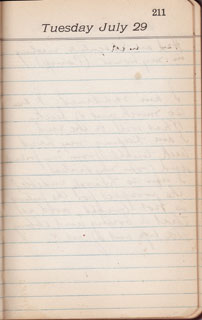

Had supper with Sister

Nettie,

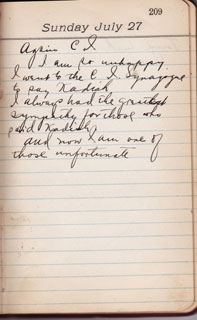

Received another bad letter

form home, eternal strife

among the children at home

I am so worried, what

can I do? My aim to bring

my mother & Fule here seems

hopeless, unless I can manage

to get naturalized early, but

the hopes are very slim, however

I’m hopeful.

In the meantime the

constant worrying is having

its effect on me, it weakens

me I think I have super-

strength when I can stand

all these worries.

——————-

Matt’s Notes

I speculated on why Papa’s naturalization status might be on his mind when he first mentioned in a couple of weeks ago, but I didn’t realize its practical effect on his efforts to bring his family over from the old country. I’m sure he would have encountered many other obstacles even if he was naturalized (Would he have enough money? Could his mother handle the trip?) but the opaque bureaucracy holding up his Petition for Naturalization obviously felt the most impenetrable. Was Papa so focused on it because there was some sort of loophole for relatives of naturalized immigrants in the recently-strengthened immigration quota laws?

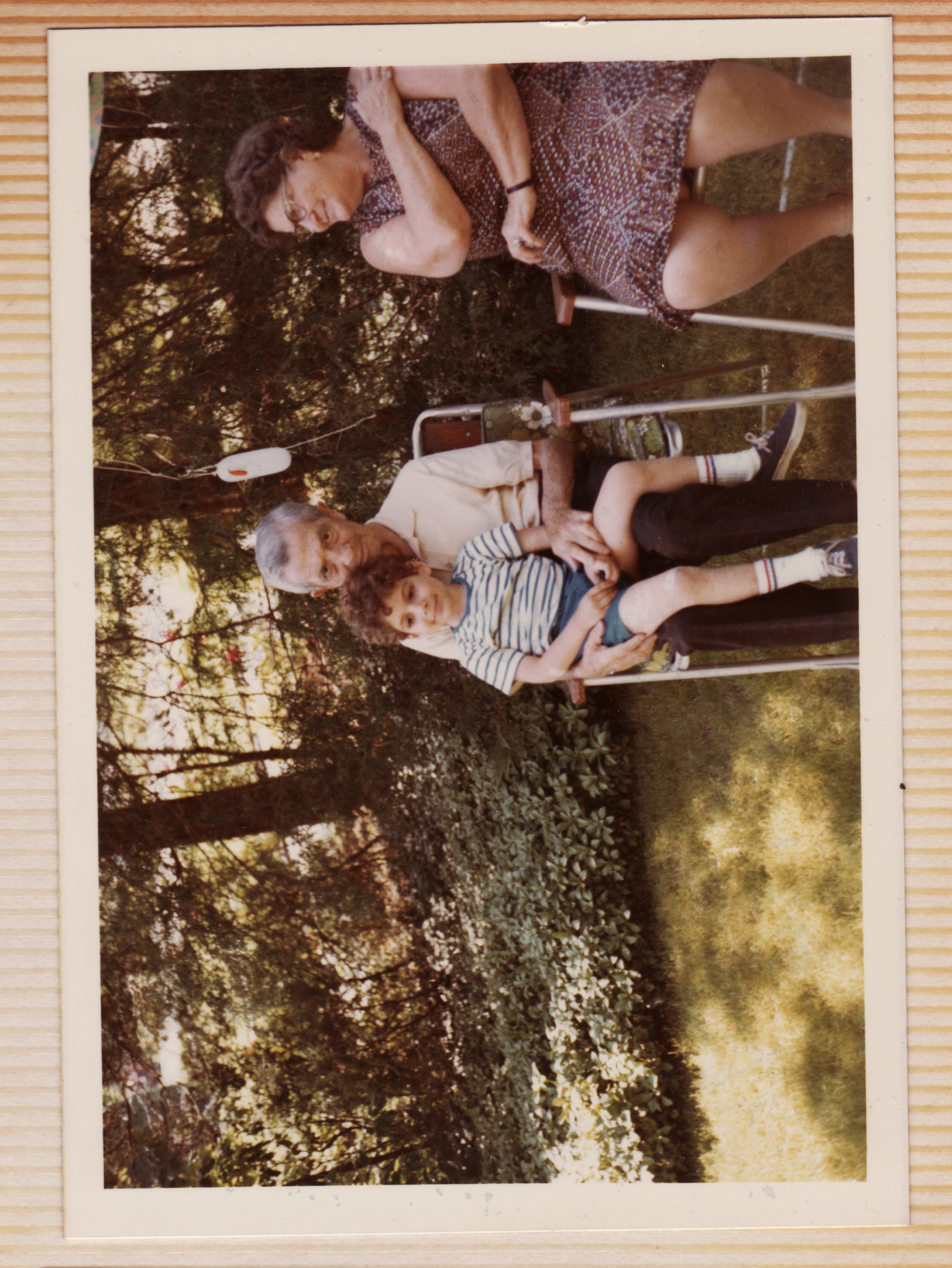

Papa never would get his mother, sister Fule or any of his other siblings out of Sniatyn, though Fule eventually made her way into the world at large through a series of marriages and adventures. (She went to Palestine after her Viennese husband just before World War II. Upon her arrival, she married a near stranger on a boat just outside Palestinian waters so she could enter as the wife of a citizen. My mother tells me the family knew this second husband only as “Mr. Abramowitz.” He was, it seems, somehow related to David Sarnoff, the Russian-born broadcast innovator and RCA founder who I’ve read about while researching early radio history for this site.)

I’m sure the worrisome letter Papa refers to contained details of his family’s financial struggles and desperate requests for more money. As we’ve discussed before, he felt compelled to provide for them all after his father died — note how he refers to his siblings as “the children” here, as if he’s really taken on a patriarchal role. Papa was naturally generous and responsible, but I think he also took on his father’s role (and worries) in part because it helped keep his memory alive. Whatever the reasons, though, his concerns as an immigrant were personal, painful, typical and timeless.