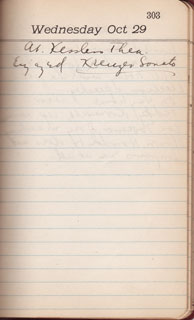

At Kesslers Thea.

Enjoyed Kreuzer Sonato

———

Matt’s Notes

“Kessler’s Theater,” also known as Kessler’s Second Avenue Theater, was a legendary Yiddish playhouse founded by the equally legendary actor and producer David Kessler. Located at Second Street, it was a linchpin of the Second Avenue stretch known as the “Yiddish Rialto” for its heavy concentration of theaters and cultural hot spots. (One

such hot spot was Cafe Royale, where Papa and his friends used to hang out and discuss weighty matters until the wee hours.)

Kessler was wildly popular among Jewish New Yorkers of the early 20th Century; his death in 1920 shook the neighborhood and the Jewish community, as indicated by the account of his funeral in the New York Times:

David Kessler, famed Yiddish actor, was buried yesterday amid the sorrowing of one of the greatest crowds that ever gathered for a ceremony of mourning on the east side. More than 100 patrolmen were needed to hold in check those who vied for places from which to veiw the cortege of the ghetto favorite…

The anonymous Times writer goes on to indulge in a wee bit of anti-Semitic caricature, rounding out the scene with a description of “picturesque old Jews, with flowing beards and white hair” along with the “peddlers, doing an active business in the sale of songs bearing the picture of the late star,” but I suppose deadline pressure can lead to insensitivity. Anyway, whole picturesque procession snaked through the Lower East Side and over the Williamsburg Bridge to Brooklyn, where “a grave had been selected near those of other favorites of the Yiddish drama and its public.” Perhaps Papa, wherever he might have been in 1920, caught a glimpse of it as it went by.

One last, odd detail: Kessler’s death was due to a “severe intestinal ailment” that struck while he was watching a stage adaptation of the Tolstoy novella The Kreutzer Sonata. As you’ll notice, the “Kreutzer” Sonata was also the name of the musical piece Papa saw at Kessler’s theater and reports on in today’s entry. (Tolstoy felt that the “Kreutzer” Sonata, formally known as Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major, was intolerably sensual, and it inspired him to write and name after it a story about the perils of carnal love.) Was this unseemly coincidence just an oversight on the part of whoever booked the concert, or was it a deliberate gesture? Did Papa, who would have read all about Kessler’s death four years earlier, get the connection?

One last, odd detail: Kessler’s death was due to a “severe intestinal ailment” that struck while he was watching a stage adaptation of the Tolstoy novella The Kreutzer Sonata. As you’ll notice, the “Kreutzer” Sonata was also the name of the musical piece Papa saw at Kessler’s theater and reports on in today’s entry. (Tolstoy felt that the “Kreutzer” Sonata, formally known as Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major, was intolerably sensual, and it inspired him to write and name after it a story about the perils of carnal love.) Was this unseemly coincidence just an oversight on the part of whoever booked the concert, or was it a deliberate gesture? Did Papa, who would have read all about Kessler’s death four years earlier, get the connection?

In any event, “Kreutzer” is a beautiful piece of music with an interesting story of its own: Beethoven originally dedicated it to the violinist George Bridgetower, who performed its premier with Beethoven. When Bridgetower inadvertently insulted one of Beethoven’s friends, though, Beethoven switched the dedication to famed violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer. It’s supposed to be one of the more technically demanding violin pieces around — Kreutzer himself said it was impossible to play and never actually performed it — but you be the judge (the video below has the first movement only; see the podcast listed under “references” for the whole thing):

———–

References for this post:

- Here’s an interesting Podcast about the Kreutzer Sonata, originally produced by the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, at archive.org.

- Tolstoy’s Kreutzer Sonata at Project Guttenberg (via Wikipedia)

- Here’s an English translation of the Yiddish stage adaptation of “The Kreutzer Sonata” via Google Books.

New York Times References:

- THE STORY AND TASK OF DAVID KESSLER; The Adventures of an Actor-Manager Who Was Trained in Russia and Rumania to Run a Theatre in Second Avenue. “Poor Butterfly.” (March 4th, 1917)

- DAVID KESSLER DIES; NOTED YIDDISH ACTOR; Stricken While Acting Role in a Tolstoy Play, His Death Follows an Operation. (May 15, 1920)

- EAST SIDE MOURNS AT KESSLER BURIAL; Great Crowds Attend Funeral Services for Yiddish Actor in Second Avenue Theatre. POLICE LEAD THE CORTEGE Many Business Houses Closed–Theatrical Unions In Procession–Bertha Kalish Delivers Eulogy. (May 18, 1920)

Here’s some more on Kessler’s Theatre from Cinematreasures.org.

———–

Image source:

1927 Second Avenue Theater Program Cover from the Milken Archive of American Jewish Music